There is far too much to say about collecting and quantifying pollen resources for one post. This post will give a bit of information about how I have collected and purified pollen for nutritional analysis in the past, and some techniques that may help with specific types of flowers. As with all things there are many ways to accomplish the same goal; however, this is what worked for me during my dissertation.

Collecting anthers

One of the standard methods to get analyzable quantities of pollen is to collect unopened anthers and allow them to dehisce in the lab over a collection container. This can work well if you are interested in flowering crops where the timing of anthesis is close to in synchrony. However, I was often wanting to quantify pollen rewards from what was currently open and available to pollinators. So, wild populations I have found that you may need to collect both open and unopened anthers.

If you plan to use static techniques to purify pollen, anthers will need to be removed from other floral tissues. The best technique for this depends on floral morphology, but I have had luck carrying a diverse set of tweezers into the field. The set I have been using lately is pictured below – it is very inexpensive, and ideal for field work because of this. I particularly like the KS-14 shape tips for removing anthers, though very fine straight tips are also nice. If you are planning on doing macro-nutritional analyses (akin to Vaudo et al 2020), you will need roughly 10 mg of pollen for technical replicates and loss during weighing. This could mean needing anthers from hundreds of flowers – yeeeeehawwww.

Open flowers: Thoughts on mesh filters

I often see recommendations to use metal mesh filters to separate pollen from anthers. I have not had success with this, as the incidental loss of pollen to the filters was too high for me. However, I have had good luck using window screen to remove anthers from some flowers en masse (e.g. Purshia tridentata). I assume this is how many commercial providers of roscaceous crop pollen do this albeit at a larger scale.

Composites: Probably the most work

For composite flowers, you can remove unopened disc florets, pierce the petals with the sharp tips of un-dropped tweezers, and then scrape the anthers away from the other tissues. All parts of the disc floret can go into the vial for later purification, but if I have found that without mechanical piercing of the petals the pollen is hard to isolate

My favorite fabs

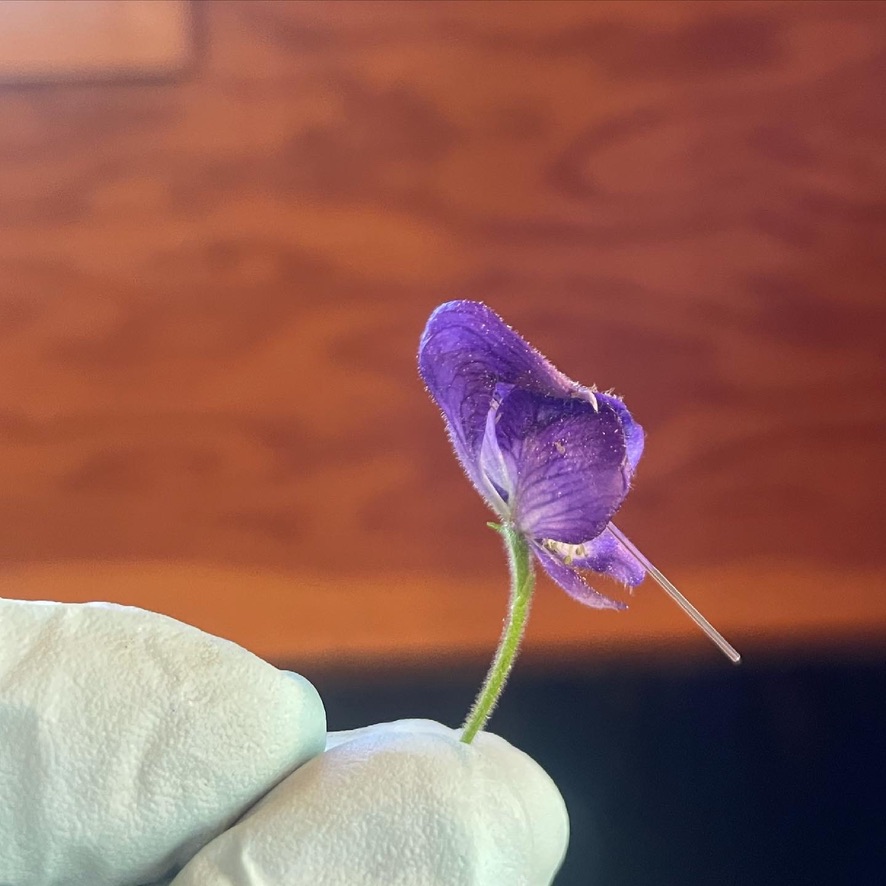

For some fabaceous plants that dose out pollen (e.g. Lupinus) I have had great success dissecting flowers, and cleaning pollen directly off of the anthers with a cleaned high quality makeup brush. For these plants it can help to hold the receptacle and base of the petals, remove the banner and wing petals, then pull back the keel petal over a vial. There is a video below.

Isolating pollen from anther parts: Static Management

My preferred method for separating pollen from anthers is via static electricity. We developed this method with Dr. Felicity Muth and Dr. Avery Russell in Dr. Anne Leonard’s and Dr. Dan Papaj’s labs when we were separating large quantities of cherry pollen from anthers. For this method you need a plastic vial about 30 times larger than the volume of anthers you are trying to process. Ideally it is large enough to fit a straight razor blade in it. The more surface area the better.

After collecting the anthers allow them to dehisce and then vortex the plastic container. Most species of pollen will adhere to the plastic, and and you can separate the anther parts by swiftly overturning the jar onto a piece of glass (or onto a second vial), tapping it once or twice with enough force to dislodge any stuck anther parts but not the pollen. You can then remove the pollen from the jar with a cleaned straight razor blade and repeat. Depending on how much pollen is in the sample and the total volume of anthers you are processing, it usually takes 3-10 cycles before the amount of pollen removed each repetition decreases.

Quantifying pollen availability to pollinators

This is a tough subject because the standing crop of pollen may not all be available to bees. Many species dose out pollen, including one of my favorite genera Lupinus, in a dynamic way that may change with humidity, time since visitation, and other factors.

That said quantifying the number of grains in a flower, and converting this to mass is possible. To do so you can remove all of the undehisced anthers from a single flower, crush them with a pestle in a centrifuge vial, remove the large anther parts, re-suspend the pollen sample in 80% ethanol dyed with basic Fuchsin (possibly plus some glycerol if pollen settles out of solution quickly), and count pollen grains using a hemacytometer.

Alternatively if you plan to count slides late you can mount a known volume of the same ethanol suspension in Fuchsin gel. It helps to have a temparture controlled hot block set to 80-82 C. This temperature will boil off the ethanol from your sample, and melt the gel without over drying the mounting medium. The recipe I use for fuchsin gel is adapted from Kearns and Innoye’s techniques for pollination ecologists (ISBN: 978-0-87081-281-1). I have left out the phenol in my work. I make it in large batches then decant into 50 ml centrifuge tubes. I warm the tubes and pour into petri dishes (about 2 mm deep) and then cut out cubes using a cleaned razorblade.

- 175 ml filtered water

- 150 ml glycerine

- 50 g gelatine (use the rest to hold up your spiky hairdo!)

- Fuchsin crystals for stain – it will take very very little of these small green crystals.

Alternatively you can acetolize a whole anthers to remove non-pollen tissue and proceed as above (I have not done this because I have no desire to work with the concentrated acids needed for acetolysis).

Other methods have been attempted to quantify realistic pollen rewards for pollinators; for example measuring pollen mass available in unopened vs. visited flowers (e.g. Arújo et al 2022, Cresswell 2001, among others) or simulated visitation especially in buzz-pollinated plants (e.g. Kemp and Vallejo-Marin 2021, as well as work from Avery Russell, Dan Papaj and Stephen Buchmann) . However I have less experience with this.