Animals do not make decisions in a vacuum and plants rarely exist in isolation. Rather, organisms’ interactions are shaped by the communities they are embedded in. Plants shape each others’ pollination, and animals compare available resources when deciding what to eat. In my work I aim to understand how community context impacts the outcome of plant-pollinator interactions in the field.

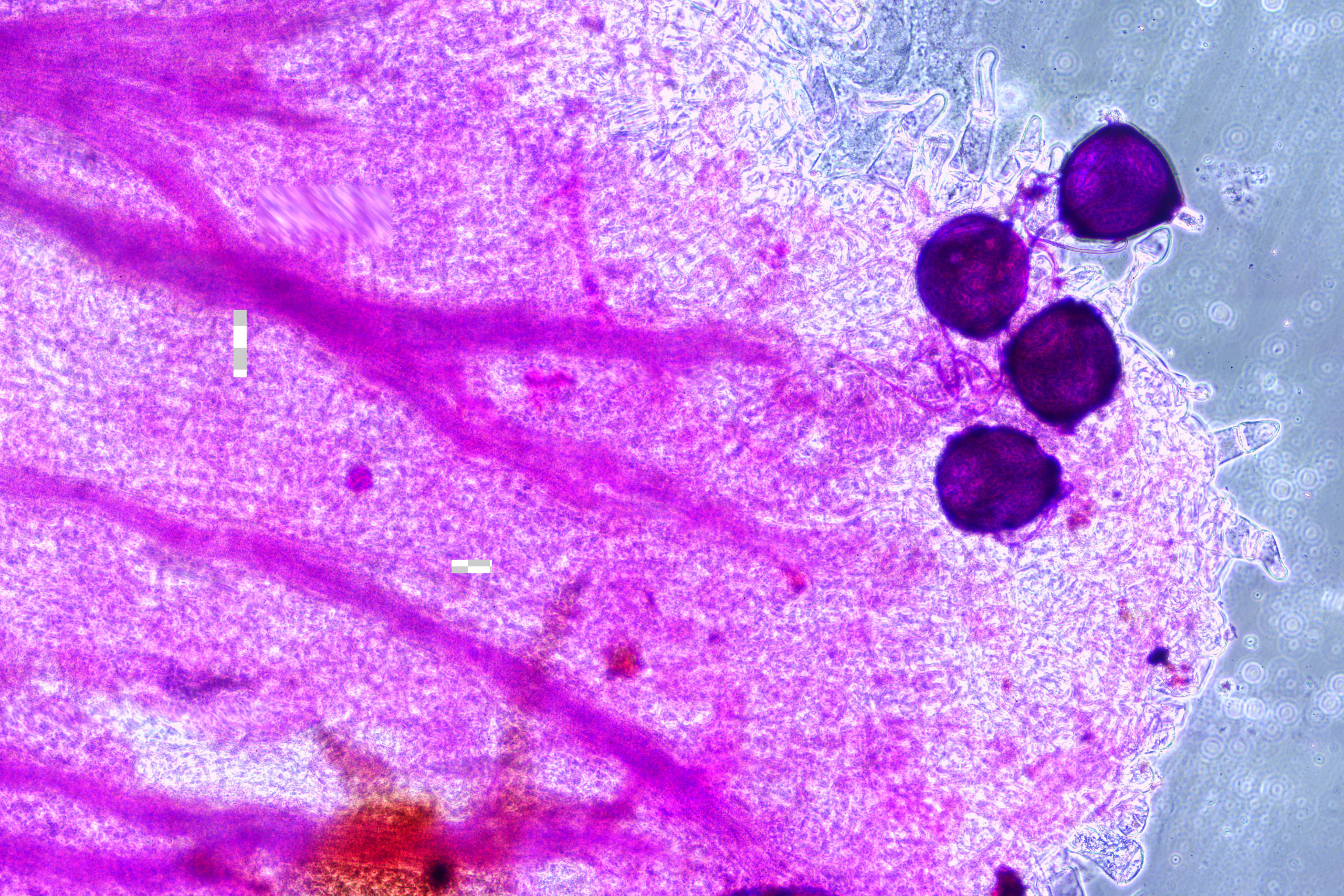

In my dissertation I established large plots (~10000 sq. m) in high Sierra Nevada meadows. With the help of undergraduate researchers, I built extensive pollen transfer networks among co-flowering species and found that reward nutrition was important in mediating pollen movement among plants. These microscopic interactions are where the “rubber hits the road” in community-scale pollination ecology. The results of this work are in preparation for publication.

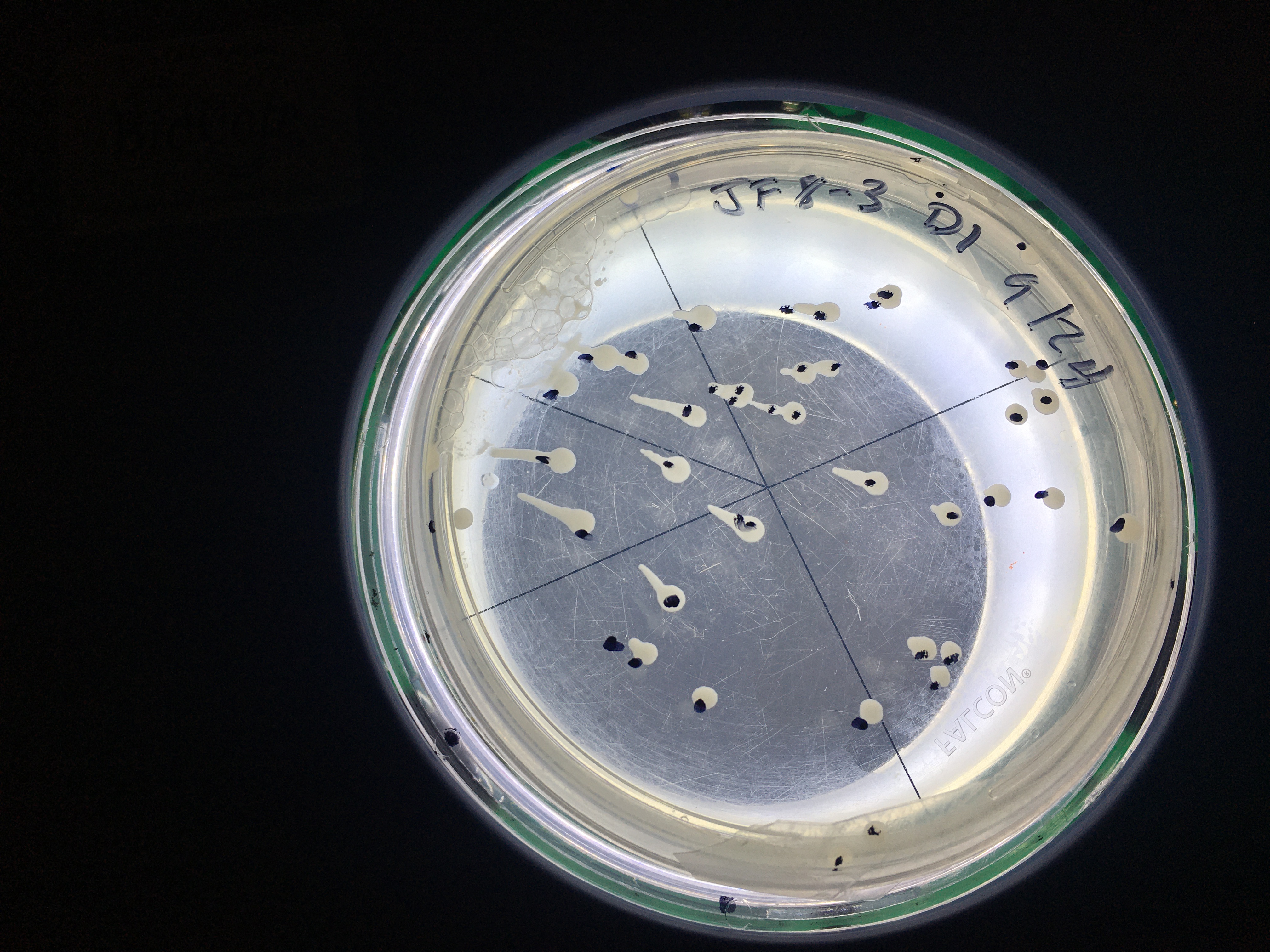

More recently I have been asking how floral chemistry impacts the microbial communities present in flowers. In the field I have asked how intraspecific variation in floral traits in Epilobium canum impacts the trajectory of microbial communities in those flowers. We found significant variation among individual plants in the abundance of bacteria and yeasts that were not driven by dispersal or pollinator visitation.